POETS,BLIND BARDS, AND IRISH HARPERS

For: YATSUHASHI KENGYO, and 'Farewell to Music' TURLOUGH O'CAROLAN

POETS, BLIND BARDS, and IRISH HARPERS

For: Yatsuhashi Kengyo, and ‘Farewell To Music’ Turlough O’Carolan.

“The Harp Is Reserved For The Soul, Not The Body Or The Bones.”

My father told me of a blind bard way-back-when in our family and so I decided to learn to play the harp in my twenties, but alas, it soon became obvious that I should have chosen this instrument at an earlier age… four, perhaps? However, I soldiered on and managed to play a couple of airs, composed, I was told, by a blind harpist, Turlough O’Carolan. Not only did I hunt for him, but discovered many others, in fact a whole group of blind poets and bards throughout Ireland, Scotland, Wales, England, and as far back as the Vedic Rishis and Shaman poets from India, blind Koto players from Japan, musicians from Persia (Iran), China, Korea, Russia, Iceland, Africa, almost every country and island one could name.

A Suzuki violin teacher who was teaching our son, led me to a Japanese woman who taught lessons on the Koto, so having given up on the Irish harp I decided to try the Koto, ordering a beautiful instrument from Japan that had a painting on the end of it, devised by my date of birth, hair, and eye colouring. It was a lovely scenic view of a snow-capped mountain and river with a dragon motif, so I was not sure why my hair and eye colouring depicted this, but I was born in the year of the dragon in Chinese astrology so some of it made sense. It arrived and I taught myself to read the numerical style Japanese music to begin lessons. The Koto teacher then told me that she had only taught blind people to play as it was traditional for them to play the Japanese harp, like a zither, originally introduced from China. It had thirteen strings, almost impossible for me to tune as it is a minor pentatonic scale and there are little blocks to move around to get the right tuning. Only the Koto teacher and Robin were able to tune the Koto.

I would pluck the strings to the reading of the notes, and she would take over the tune to teach me, as she would a blind person.

The Koto was originally played at the Imperial Court in Japan. A famous blind Shamisen player known as Yatsuhashi Kengyo (Kengyo is an honorary title given to highly skilled blind) was the first one in the seventeenth century known to play the Koto, outside of the Imperial Court setting, making it available into traditional Japanese music. His teacher was Hasui, a court musician. I wondered if anyone got into trouble for the quantum shift from Inner Court to the outside world.

I still have my Koto, and did manage to play some compositions, one being the lovely melodious tune about the falling leaves of the cherry blossom tree that appears in every Japanese, Chinese, or Korean film.

However, travelling so much prohibited the continuity of my lessons although I did get to visit Japan often and marvel at the astounding cherry blossom trees, and although I had a fondness for the instrument, it remained at home when I had wings on my feet. I love the wind-chime sound of the music. It takes one on a journey, reminding one of waterfalls, rippling streams, soft breezes, and dancing.

Always interested in spirituality, the astounding numbers of the blind composers gave me reason to think that deprived of the sense of sight seemed to give these special souls access to the Muse, with such concentration on the inner realms that they could only produce wonderful sounds to stir the souls of others.

One blind musician whom I met, called Harry, from Scotland, played the bodhran in the Wallace Clan, (descendants of William Wallace from Braveheart fame). They wore the long kilts, were in the Braveheart film, and played great Scottish music. Harry, who had been blind from birth, told me of his fear of birds, that could swoop and fly from the space above with no Earth ceiling at all. Put into those words, I understood his blindness and his fear immediately. In further conversation, he felt there was infinity on all sides of him, except for the ground beneath his feet, and he wondered if there was an edge to it all. As a ‘seeing’ child, I thought so too.

My late husband spoke of a brilliant blind keyboard player called George, who toured with the Bee Gees. One evening after the performance George wished to discuss the next night’s performance of a particular song with Robin and invited him to his hotel room. George answered the door in complete darkness because of course he had no need of light, and Robin duly complied with the situation and said it was a surreal experience discussing and playing the notes in the darkened room on a keyboard. I asked him why he didn’t switch on the light, but he said it was normal for George and for that hour Robin wished to relate to the world of George, to know what it felt like and how to be creative within it. He said: “I often close my eyes to listen when composing on an instrument. It helps me hear better.”

However, negotiating the furniture would be a different challenge altogether, I would think. He did add that they got some strange looks when room service delivered tea, so the light had to go on.

Obsessed with poetry and writing from an early age, I did prefer to write at night and still do. The Irish counted their days in nights… a sennight was seven nights or a week, and a fortnight represented fourteen nights, two weeks. So maybe the darkness holds a secret. I love writing at night.

I realised that poetry was a way of expressing any emotion or giving vent to feelings and opinions in a way that became acceptable, like keeping a diary. Poetry was especially potent in Ireland, beyond the world of journalism, beyond the current political landscapes, but it also had a dangerous darker side bordering in satire and could alter history in such a way that even Saints tried to stop the satirists. Kings who revered poetic praise at first, feared the exposure later and paid great sums to appease a few tyrants who flouted the strict rules of Irish poetry in the early schools. Satire wrought shame and guilt on those at the receiving end, whether deserving of that judgement or not, and brought misery to the recipients, relatives, and friends.

The ancient Irish used rhyme well over two thousand years ago to commit their epic poems to memory. Many of the Ollamh masters took twenty years to become great historians and composers of metre. They also recited the Ancient Laws of the land, set up by the Brehon judges who specialized in judicial, mediative and arbitration laws. These laws were really a moral code and guidance to keep citizens in a fair society of sorts. The bards were the news callers of the day.

In Rathfarnham, County Dublin, there is what is known as the Brehon Chair or the Druid’s Table, a Megalithic site, used by the Archdruid for yearly making of new Laws and for the keeping of old ones. One of the female lawgivers namely Brighid was a blind seer used for her wisdom, fairness, and ‘seeing’ abilities. The Brehon Laws were oral and memorised, repeated by poets throughout the land to different clans.

In the Irish Schools of Poets, the students were taught about four hundred different kinds of metre, depending on the level they needed to attain. Twelve years was an average length of time for the Fili, ( Seer in old Gaelic) and the poet warriors had to reach a certain level before they could lift or use weapons, until they had been schooled for this amount of time. Imagine the armies of today having this kind of training! The poets must learn the history of all the known clans and were invited by chieftains and kings to understand the differences between good and bad seed among the clans. The warriors had to define:

Who should live and be protected in battle?

Who should be maimed?

Who should die?

Many bad-seeded warriors were maimed to prevent them from rising to hold the title of King or Chieftain. A King had to be of sound mind and sound body.

Cormac mac Airt for example lost an eye, not in battle but by accident after many years, and had to retire as High King (Ard Righ) at Teamhair (Tara), because of this imperfection.

The poets travelled from camp to camp, and from battle to battle, their learning and their observance as Seers protected in war by the colours they wore. They were the true genealogists. Many kings died in battle, but few poets were ever killed. It was absolute sacrilege to kill a poet. The bards were entertainers, historians and storytellers who kept up the morale of the warriors and the families. They trained their minds to such an extent, memorising so much, that they naturally became sages and the Ollamhs especially could use psychometry and open their psychic abilities to read other’s minds and make predictions.

After the death of an ollamh or skilled poet, the master Ollamhs would try to trace the souls who would return to continue their learning, showing a natural penchant and aptitude for poetry and being ‘seers’ as children. Once sought and found, they were fostered and taken into the schools to begin their training to reopen the gateways to their past teachings. Ossian, the son of Fionn macCuillhan (Finn MacCool) was such a poet, who lived for hundreds of years believed to having been birthed again and retaining his previous knowledge. It was a Druid belief that death was but the recurring middle of a long life. Talent was considered to move with souls, not just genetically from ancestors or from brains, but from the grooves of learning and skills indented in their soul-memories like a record during their lives.

However, if a poet should satirise a man unfairly in his absence, or send another of his pupils to do so, while he hid away, or if a laughingstock was made of a king, the fine was enormous that not only affected him but his school of learning. He would be scorned and made to suffer for the crime. The Brehon Laws were adhered to harshly and were unrelenting to a wayward poet.

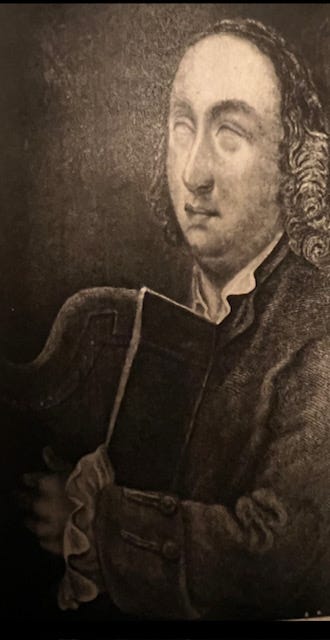

In the year 1670, Turlough O’Carolan was born at a place called Nobber, although some say it was a neighbouring village in County Westmeath. It was said that, because of his loss of sight to smallpox at around eighteen years old, he had honed his memory to such a great degree that if he heard a tune just once, he had the ability to remember it forever. In the beginning he was a harpist learning his craft but had a unique gift for melody and arrangement of chords that excited the senses with happy, yearning, or lamenting riffs. His popularity grew quickly throughout Ireland. He had the propensity to create new tunes with astonishing ease. Repeating the unique Baroque style melodies and the lyrics of the songs on his travels, playing in many different places gave credence to the works, so that they were in the proper Irish way passed on in story-telling tradition, although they were not traditional folk songs or dancing music, but more classical, totally rare. These were later notated in theory by a Master of Music, Edward Bunting, and played by harpers, violinists and pianists wishing to honour O’Carolan. There were some notators who travelled or lived in the big houses who could make manuscripts, often squirreled away for posterity in the keep of Ladies of the house or older women, some widows.

At the home of an Irish nobleman, the eminent composer Geminiani was present and Carolan challenged him to a trial of skill. Geminiani played a tune on his violin that Carolan had not heard before. It was Vivaldi’s Fifth Concerto. After playing it through once, Carolan repeated it instantly on his harp, then said he could in minutes create a Concerto of his own. To the astonishment of the company, he did so, and this piece has been forever known as Carolan’s Concerto. He took a few moments and composed it in his head by touching the buttons on his coat, and using them as lines with spaces in between, committing the patterns to memory and then instantly played it on his harp. This was something he often did, and it was a well-known habit observed by his friends. The buttons were his type of braille for remembering or writing music.

A professor, Dr. Grattan Flood refuted the story of the way the contest was made, writing in his History of Music, saying that Geminiani could not quite remember meeting Turlough O’Carolan, (I would have thought everyone would remember!) but wished to test the theory anyway, and sent him a Concerto he had composed but deliberately inserted a few mistakes in it. One wonders how this was done without him being present to play it, remembering that O’Carolan was blind.

Carolan listened to it and said that it stumbled and tripped and limped in a few places, then suggested improvements which were duly given to Geminiani, who then proclaimed him a genius beyond genius.

On March 25th, 1738, Turlough O’Carolan was back at the mansion home of his old Patroness Madame MacDermott at Alderford, near Boyle. He had fallen ill and after entertaining, asked for his harp to play his last composition, a plaintive piece he called ‘Farewell to Music’. Then, immediately afterwards, he lay down to die. (Farewell to Music is favoured by many harpists today).

Hardiman described his funeral.

His funeral on the borders of County Sligo was one of the biggest ever funerals in Connaught, attended by hundreds of mourners and musicians playing their harps through the County. On the fifth day, after his death, the wake went on with about sixty of the clergy from different denominations. Patrons were also present. Gentlemen with their families who had honoured him in life, came there. All the houses in Ballyfarnon were occupied by people from different surrounding Counties and the fields were full of tents and wagons, vardas, and makeshift shelters. Barns were made available. Everyone was in tears and the keening was heard everywhere. There were blind poets attending, and he was proclaimed the Head of all Irish Music. He was buried in the East of the old Church of Kilronan beside the MacDermott vault. Mrs. MacDermott stood with all the women to mourn the loss of her ‘poor gentleman, the best bard in Ireland’.

There was a curious letter by a witness written at the time that described the mound of stones on the grave and that the skull of Carolan was on the side in a niche with an interesting indentation on it, marking him for the bardic poet he was…then later it was stated that his skull went to Belfast as a relic and is currently in the possession of a Masonic Lodge, having undergone strange but natural changes. It is apparently used in some very sacred ceremony of the Order.

There is a lovely marble bas-relief in a prominent position in Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, placed at the request of Lady Morgan to have a permanent monument to him. She was a great patroness of the harpers. Turlough O’Carolan is shown playing the harp, as the last of the Irish bards.

The bards and poets, blind or not, had very interesting lives indeed, according to Charlotte Milligan Fox, herself a brilliant harper, who wrote a rare book on The Irish Harpers, venerating the work of Edward Bunting. He rescued from oblivion the last authentic record of ancient Irish Minstrelsy, hearing the strains of the last minstrels, to make sure ‘that the poets and blind harpers of Gaeldom could never ever be forgotten’. She thought it remarkable that the city of Belfast was responsible for making sure these records were kept for the whole of Ireland, given as she quoted: ‘Belfast was the capital of the Ulster Plantation Colony!’ Charlotte was a sister of the first Protestant Nationalist Alice Milligan, a renowned poetess, whose poetry is priceless, and it was documented that William Butler Yeats revered her talent. He visited her, encouraging her to write plays and seemed to admire, but had a certain twinge of jealousy, about her poetry. The sisters were born in County Tyrone and lived near Omagh, and my interest in them was stirred just by that fact alone. I was born in Tyrone, near Trillick, Omagh being the nearest principal town.

Edward Bunting and Thomas Moore were the collectors of the Irish melodies, although Bunting went to hear the harpers and being an organist and pianist, (even constructing pianos), he notated the music and produced his findings seven years before Moore distributed the precious songs and airs that were played all over Ireland, Britain, and Europe.

Another blind harper, namely Hugh Higgins who came from Tirawley, County Mayo, was recounted in Arthur O’Neill’s memoirs, ‘Life as a Gentleman Harper’, in a story about Higgins, his respectable, now deceased friend, who came to the assistance of another blind harper Owen Keenan at one of the harp festivals. Owen was a bit of a blind Romeo and a rascal. The incident happened near Omagh. Owen Keenan, born in 1795, it was said, was of the reckless turbulent class but known as a fine teacher of the harp and taught Arthur O’Neill himself when resident at Augher, County Tyrone. Keenan engaged in romantic frolics and had various escapades, one of note here, although it is fair to say he was most recklessly in love.

At the prime residence of a Mr. Stewart, near Cookstown, he became enamoured with a ‘French governess with the silken tongue’, who resided with the Stewart family, and blind though he was, contrived to make his way to her apartment by a ladder up to the window. The Master of the house was not amused and became justly offended. He caught him in the act and had him committed to Omagh gaol (jail) on a charge of ‘housebreaking’, not wishing to shame the weeping governess, although it was known she had a love-hankering for the harper.

Hugh Higgins, also blind, from a very respectable family, hearing of his mishap, came all the way from Tyrawley, County Mayo. He travelled in a better style of carriage than most others of the fraternity and posted down to Omagh forthwith. His appearance and retinue procured him admission to the gaol and adjoining house. The jailer was away from home, but his wife was there and loved music and fine cordials. It was reported that these harpers were particularly fluent in humouring the weaknesses of one who had once been a beauty. The result may be imagined. The blind harper after plying her with the sweet cordial, while she was oppressed with love and music, stole the keys from her pocket, then made the turnkeys very drunk and let Keenan out.

While Higgins stayed behind like another Orpheus charming Cerberus with his lyre, Keenan ‘marched out by moonlight merrily’ with Higgins’ lamp boy on his back to guide him over a ford of the Strule. (The river flowed close under the gaol walls.) Foolishly, he took his route directly back to Kilymoon again, scaled the house once more, ladder or no, and finally, after yet another commitment for ‘the ladder business’, as O’Neill calls it, plus a narrow escape at the County Assizes, carried off his silken-tongued Juliet and married her no less. Higgins, a man of respect with his lamp boy saw no trouble at all for their dealings.

However: “Keenan, always getting into scrapes, emigrated to the New World (USA) after marriage, whereupon his French wife unfortunately proved unfaithful!”

There were many women harpers and poets, also artists who sketched the most famed of the blind harpers. Rose Mooney was one of O’Carolyn’s favourite harpers and composers who played at the Belfast Festivals and at the famous Granard Balls. A Harp Society was formed in Belfast.

In 1781, First Ball At Granard. County Longford.

Harpers present: Charles Fanning, Arthur O’Neill, Patrick Kerr, Patrick Mag, Hugh Higgins.Charley Berreen, and Rose Mooney.

The blind, talented, and resilient Rose Mooney, an itinerant Irish harper from County Meath, born in 1740, composed a piece called Planxty Burke and received a prize for this. Rose was taught to play on the harp by Thady Elliott. She was adored by many, always welcome in the houses and at the Granard Balls where she won prizes at each one. She visited Belfast several times at assemblies of harpers.

There was a crack in the belly of her harp, with a makeshift fix of canvas or pasteboard, but it was said, the instrument could outdo any other new harp with its sonorous tones, having three extra strings and copper strengthening on three strangely placed harp timbers.

Arthur O’Neill said: “She pledged her harp, petticoat and cloak.” He was exposing the antics of Mooney’s maid, Mary, who took advantage of her blind mistress by pawning her items every so often, any article she could, to buy herself alcohol, and whose uncommon desire for drinking was unlimited, anything to raise half a pint! Mary led poor Rose into seedy establishments that he quoted: “were inseparable for poor blind harpers.”

“I acquit of any meanness on your own account, poor Rose, as your guides and mine have led us into hobbles which we poor blind harpers have to get out of and afterwards laugh at. But we in general think that it’s better for people in every situation in life to have about them the rogue they know than the rogue they don’t know.”

Charlotte Milligan Fox discovered the writings of Edward Bunting. Bunting who travelled the whole of Ireland to find the tunes and airs of all the harpers, noted that Carolan’s Planxty Charles Coote was inspired and taken from Rose Mooney.

Bunting travelled around on Miss Mary M’Cracken’s mare, but he didn’t ride the horse. He had a vehicle of some sort, perhaps a trap or half-covered wagon. He rode from Belfast to Sligo and alluded to the ‘collar’ on the mare, worried about the mare’s neck getting a bit rubbed, so he would rest at the inns and houses along the way. He collected a poem from an old lady in Dungannon. It described the Battle of Aughrim and he said the tune was similar to one he heard women sing when they lamented over the bones of the dead. She told him it came from the up-country bards, the Munster school of poets, the Kerry gentry. Many manuscripts that he collected and copied were kept by elderly genteel women or widows, all the way from Belfast to Sligo to Limerick.

Charlotte related a quote: “A queer set of fellows were those bards, blind or no, one hour rollicking in the Shebeen House and the next seated in some tradition-haunted rath, bewailing the woes of Innisfail and the persecution of the old religion! Moore’s songs were made for the ballroom and for gentle maidens who sit at the piano, manufactured by some London house. But before Moore sang, our grandmothers at the spinning wheel and our great grandfathers, whether delving in the fields or shouldering muskets in the brigades, sang these consecrated versions to keep alive the memory of Ireland, her lost glories, and cherished aspirations.”

Despite the slight, Moore faithfully preserved the melodies and songs for posterity.

Bunting lost sight of none of them, neither did O’Neill who told us that after a lifetime of creating beautiful music, Rose Mooney perished miserably as a victim to drink sometime after the French Invasion at Killala in County Mayo 1798. The rebels forced open the loyalists’ spirit stores (probably whiskey and a type of home-distilled poteen often sold by widows to make a living), and it was thought that Mary led Rose into some of them. Rose was much respected at one time, but it is certain that her maid was the principal cause of her falling into disesteem, as Mary would, and did, sacrifice the reputation of her mistress for a glass of whiskey and the hard stuff.

Rose Mooney’s loss was felt keenly and mourned throughout the Harp community. She had played at the Balls, composed songs, and strummed beautiful melodies, Bunting noting her work and Carolan’s Planxty in 1800.

Many Harpers could also play the violin, the fiddle, and pipes, their means of making a living at funerals, entertaining at weddings, and folk dances, but:

The Harp was reserved for the soul, not the body or the bones.

Arthur O’Neill, from the Chieftain O’Neill’s of Tyrone, was proud of his heritage, himself a blind Harper, and his memoirs have contributed to this fraction of considerable work. He had been the intimate friend of Acland Kane who played before the Pretender, the Pope, and the King of Spain. He himself had played on the harp of the Ard Righ, High King Brian Boru’s jewelled harp, taken out of silk, and strung for the occasion to play music through streets of Limerick in 1760.

(Ann O’Neill, a mother, is buried in the old graveyard near my family home. She had either 12 or 21 children, I could not properly read the faded stone of the Celtic Cross covered in moss, but everyone knew she had carried Kings and Chieftains for Tyrone).

(An artist and poet who painted Belleck pottery is buried nearby by the name of Eugene Sheerin, born 1856, a new stone recently erected, with, in attendance, a brilliant Irish poet and bard today: Stephen Murphy from Leitrim, performing at the ceremony.)

Edward Bunting presented his works through Lord Belfast to Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort Albert, giving such recognition to the Irish airs and compositions by male and female Harpers.

Buxton, Sept.8th.1839 to Edward Bunting.

“Sir,

I have received the Queen’s commands to inform you, that she has been graciously pleased to approve of your dedicating the forthcoming Volume of your Irish Melodies, to Her Majesty,

I have the Honour to remain, yours obediently,

BELFAST.”

And Charlotte Elizabeth Milligan Fox, a skilled Harper herself, spent a lifetime researching and honouring them all. To her, we can be eternally grateful.

Charlotte in later years was subject to some deafness and Bunting received a letter about Charlotte Elizabeth, in a rather critical vein, from a Dr. MacDonnell sending a poem written by an obscure person, as if Charlotte were pallid and delicate and he pictured her thus: (but was he referring only to Charlotte?)

“Upon a rock Ierne sad reclined

And gave her locks dishevelled to the wind,

Her cheek, which once the crimson morn displayed,

Was pale as Cynthia, daughter of the shade;

Her harp, unstrung, was careless laid aside,

She only listened to the murmuring tide,

And sighing gale, which scarce was heard to blow,

But seemed from sympathy to breathe her woe.”

Charlotte Elizabeth by this time was indeed losing some hearing and was being slightly scorned as the ‘Orange’ authoress, no longer able to hear her harp, and daring to research the Catholic Irish music, even though her sister Alice was one of the first Protestant Nationalists at the turn of the last century. So absurd, when religion never solely defined the Harp, played for thousands of years before the Christian religion and then later used in all religions, thought of as other-worldly or Heavenly. All music of any kind goes beyond colour, caste, and creed, and nor is there a difference seen by musicians North and South, East or West. But the poem itself had a hidden meaning where she was being portrayed as Erin, (Ierne) Ireland, herself, lamenting the loss of the great Age of the Harpers, lamenting the changes, many of the harpers becoming wandering itinerants, relying on movement and kindness, no permanent home, going from place to place, no longer being sought after and given shelter in the big houses, too much war and then famine, exile and emigration, but Ireland will never lose her music or her voice, her poetry or song. There is no magic charm greater than music and language, and no greater Nation than Ireland to keep this in its heart.

DWINA ***

PS: A wonderful Irish bard today (not blind) is Stephen Murphy from County Leitrim in the style of the Ollamh who commits his poetry to memory. Look him up. He recites a poem called The Morrigan.

PPS: The Blind Poets, an Irish Band from Cork is also a delight for the ears.

Just listened to Garrett Barry play Old Hag in the Kiln! Brilliant. Thank you.***

Thank you Niccola. I like to bring History alive again xxx